The Aurat March provides a much-needed counterpoint to the strategic blindness in the society to women’s oppression

Saira Minto, Minerwa Tahir, and Amna Mawaz Khan

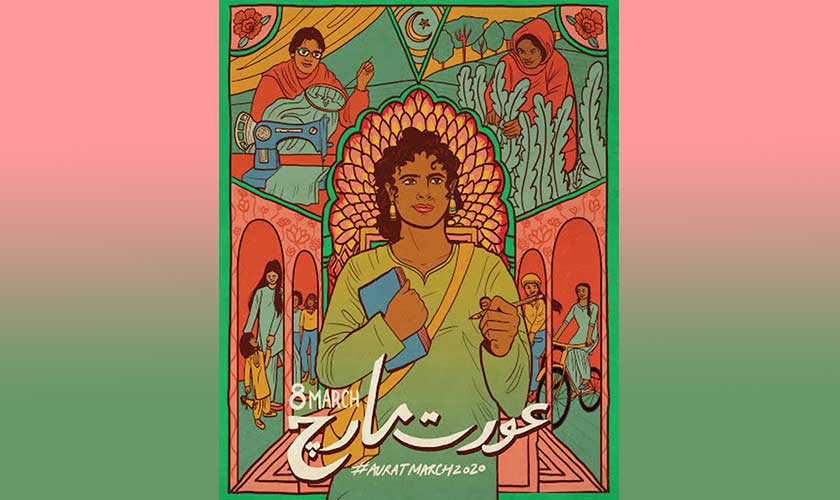

In recent years, Aurat March has become one of the most visible expressions of a growing women’s movement in Pakistan. From 2018 onwards, major cities of Pakistan have witnessed the Aurat March – thousands of women, gender minorities, men and children – who take to the streets and march on International Working Women’s Day on March 8.

In Karachi and Lahore, the Aurat March is organised by an alliance of mainly radical-feminist and liberal-feminist forces, including leading figures of NGOs who all agree to leave behind their individual banners and unite under the one banner of Aurat March. One organiser from Karachi is quoted in an Al Jazeera feature to have said last year: “The issues facing women today are about equality in public spaces, right to work, safety at the workplace, and most importantly, infrastructure support. The previous generation fought for political rights”. Another sentiment that drives Aurat March is the popular desire for equality in private spaces such as the family, and the sore need for recognition of the woman as an autonomous being, and not merely an unpaid worker or showpiece within the family.

Aurat March is not the only symbol of women’s organizing in the present period. In Hyderabad and Islamabad, the Women Democratic Front, a socialist-feminist organisation, organises the Aurat Azadi March. Some of the demands of this march have been for an end to violence against women, legislation that protects the rights of women and transgender people, minimum wage and other legal protections for the informal sector, an end to privatisation of, and greater investment in health and education, particularly for women, hostels for women and day-care facilities for the children of working women, construction of low-income housing and an end to the campaign against informal settlements, an end to military operations, and the safe and early return of the missing persons.

Both these marches increasingly solicit the support of working women’s associations, such as the Lady Health Workers’ Association, Nurses’ Association, and the Pakistan Trade Union Defence Campaign. The Aurat March 2020 in Lahore has developed a robust strategy for drawing working-class women through outreach and mobilization, as also has the Women’s Democratic Front in Lahore. One can say that the women’s movement is coming of age.

Why do we need a renewed women’s movement today? Just last night one of us was asked this question by a well-meaning young man. She launched into a description of the state of women’s rights in Pakistan where women, both economically, legally and culturally, occupy what we can term a second-class citizenship. The state of affairs is so pathetic that this holds true for women even from the middle classes. Women students who are entering colleges and who along with men their age represent the future of the country in so many ways, have to confront a range of obstacles from harassing teachers, incompetent administration, unreasonable curfew hours, and as we have recently seen extreme sexual surveillance, which is daunting to say the least, to complete their education. It was disturbing, that this young man did not seem to hear any of what she was saying. He picked up the only point that he thought he had an answer to – that men are physically stronger than women – in order for him to try and justify the gendered division of labour. It again became starkly evident to us that Aurat March provides a much-needed counterpoint to the strategic blindness in the society at large to women’s oppression. It does this through its display on its posters, of types of discrimination, harassment, poverty, and exploitation that women face on a daily basis.

Aurat March is also needed to speak boldly of women’s liberation as the basis for everyone’s liberation. Bringing sexuality out of the privatised sphere of the home during the 2019 Aurat March, in particular, was a radical achievement of the women’s movement in Pakistan. Sexuality, a topic that given its ‘private’ nature was never spoken of in the public domain, was brought by the march out of the confines of the home and private life and laid bare as a site of oppression. Consequently, the right wing launched attacks against the organisers and participants on mainstream and social media. Death and rape threats were issued. Yet many men and women, when engaged as to the meaning of the posters and placards, also agreed with the need to liberate sexuality from the confines into which it has been thrust.

With the increasingly deepening economic crisis in Pakistan, and given the IMF conditionalities which have brought about much worse conditions for the working poor and lower middle class, the women’s movement has even more fronts on which it now has to fight for women’s emancipation. Here much re-thinking has yet to be done. A demand such as “equality in public spaces”, while reasonably pitched against a male-dominated public sphere, does not begin to tackle the dimension of the structural economic problems that imprison working-class women.

As WDF organises for Aurat March, we are keenly listening to the working-class women we meet. A powerful demand could be the establishment of price committees comprising working-class women. Our movements ultimately have to be anti-capitalist as not just in Pakistan but also across the world capitalism exacerbates all forms of oppression, be it sexism or racism, and does not offer any economic progress for Pakistani working people. Our movements also ought to be demanding system change as opposed to climate change, and democratize the economy under workers’ control. Like the smog that does not care for borders, our movements also need to stop caring about them. Finally, real success will depend not on the mere existence of women’s organisations and marches, but on women’s working-class leadership of a large labour and working people’s movement, which will fundamentally challenge capitalism, patriarchy, national oppression and racism, and put forward alternative solutions to stop environmental devastation in our cities and countryside.

The writers are members of the Women Democratic Front, Lahore

This piece was first published by The News, on March 01, 2020.