Aurat March Lahore reflects on how building feminist futures begins with strengthening our feminist collectives.

This essay is the result of collective authorship of volunteers from Aurat March Lahore. In our writings, we reject individualised notions of idea-ownership and labour, preferring to speak as a collective based on a consensus-driven writing process. Thus, throughout this essay, ‘we’ is used to reflect one collective voice of the organisers and volunteers of Aurat March Lahore. We recognise this perspective is limited, as the Aurat March Lahore extends beyond the volunteers who organise it and holds political meaning and possibility for many.

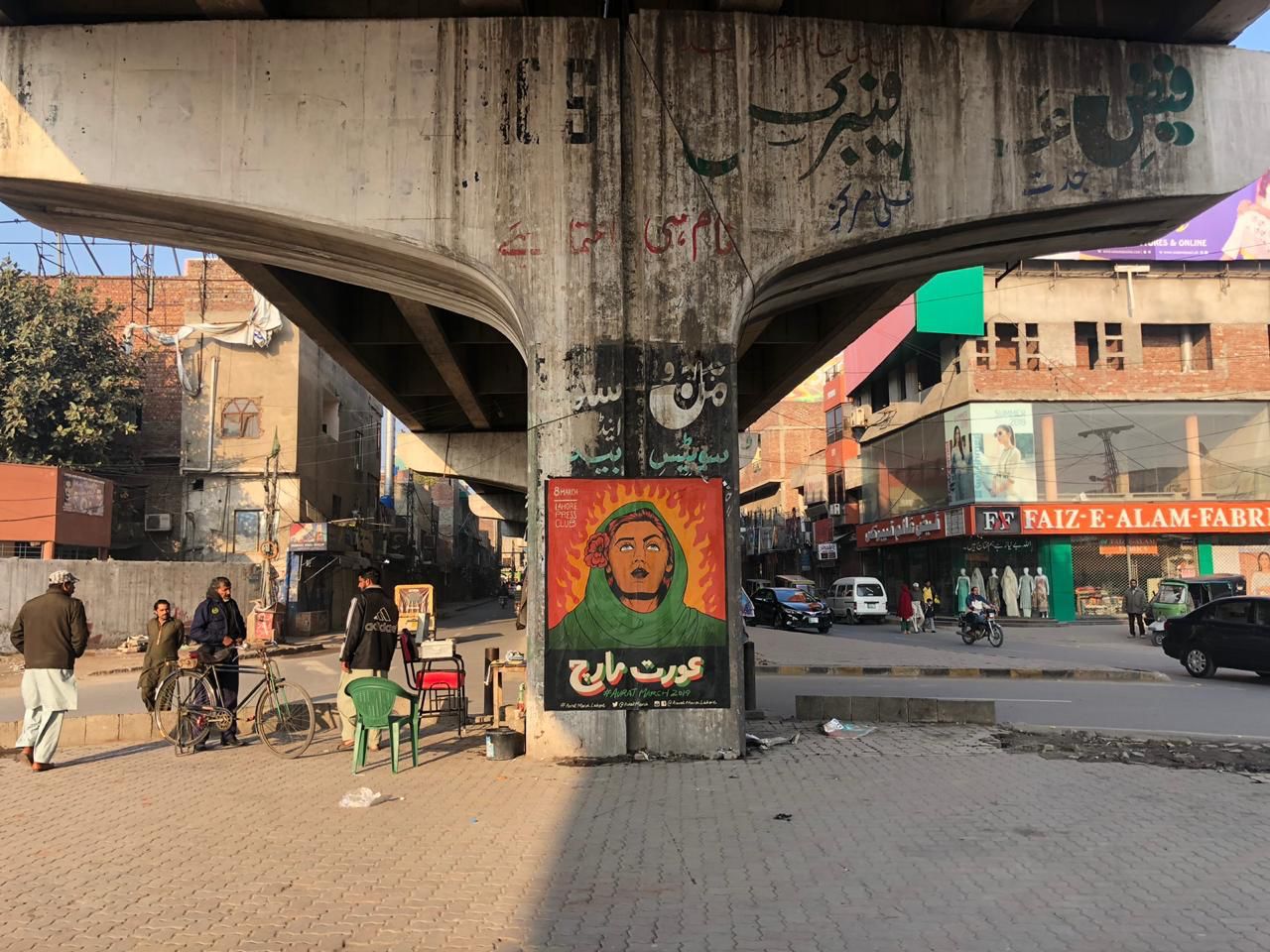

While Pakistani women have historically used the march as a means of protest, the emergence of Aurat March in 2018 has received outsized attention within the national consciousness. Thrust into very public conversations about rights over our lives and bodies, Aurat March as a collective spent much of its energies countering backlash for the first four years. Dealing with issues ranging from the trivialisation of our politics to safety threats, we were defining what we stood for in real time.

Six years later, we are confronted with questions: “What has Aurat March Lahore achieved?” and “What difference has it made in the struggle for feminist and collective liberation?” Although these questions of success or failure are often meant to belittle our labour, we believe there is value in reflecting on the direction our movement has taken and the political choices it has made. Aurat March means so much to so many of us: it helps us make sense of the world around us, and for others, it provides a sense of community, albeit flawed and limited in its scope. On the other hand, as a collective that takes up so much space within the movement, Aurat March Lahore must be accountable to the communities it strives to speak for and stand in solidarity with.

Driven by this reflection, we sought to define feminist politics in Pakistan as our theme for Aurat March 2024, which included understanding our role within the larger political landscape. Our reflections uncovered the nature of power structures we confront as we seek to dismantle capitalism and patriarchy, but also reflect on our own power.

As a collective, we have often eschewed questions of power. Our original internal structure was one of denial of power as we opted for a completely flat structure with no hierarchies; rather, it consisted of a pool of volunteers with equal decision-making power. We quickly learned, however, that we cannot ignore the insidious power structures and hierarchies of class, gender, and (dis)abilities within our own collective. Over time, we saw the non-hierarchical structure morph into power being consolidated into an organising committee consisting of the most active volunteers, who wielded decision-making power. While the committee sought to make decisions through consensus, we learned these invisible hierarchies remained between the organising committee and volunteers, and within the organisers based on class, gender identity, and disabilities. With power clustered around these markers, those with greater resources, time, and mobility were able to work more and command more decision-making power. We learned that denying power structures within organising did not erase them, and simply acknowledging them was no substitute for building political trust. Mechanisms of honesty, accountability, and reflection were required to hold the weight of our shared work.

We also quickly realised that within the movement, we often denied our own power as a way to escape accountability. As difficult as it is to admit, we leaned into the backlash that Aurat March faces to shield ourselves from genuine critique. Although critiques about our class politics may often feel disingenuous, our defensive response precluded genuine conversations about the infrequent participation of working-class women in our core organising committees.

Shedding capitalist, patriarchal frameworks

When we question what Aurat March Lahore has achieved in the last 6 years, we must first ask which metrics to use in order to evaluate our successes and failures.

Capitalist logic compels us to prioritise quantitative metrics to measure our impact because they offer quick, clear, and tangible evidence. Metrics such as the number of participants at a demonstration, what kinds of communities we worked with, and social media engagement, only capture a narrow slice of this impact. This raises a critical question: how do we deal with the paradoxical tension between valuing and measuring our visibility, versus seeking deeper, unquantifiable cultural shifts—those fundamental yet often intangible transformations essential to dismantling patriarchal oppression?

Do we use the hyper-corporatised or NGOised logic of productivity, which quantifies social transformation and impact through performance indicators? Are online views and followers truly indicative of our achievements, especially when skewed algorithms continue to reinforce the status quo and suppress dissent? Or should we instead extend ourselves grace and find meaning in the relationships and solidarities we have nurtured across communities? Considering that Aurat March is in its nascent stage in the arc of Pakistani history, is it even reasonable to quantify success at this juncture? These questions catalyse our critique and resistance towards reductive evaluative frameworks, urging us to redefine progress in ways that honour the profound, often unseen cultural shifts.

Attempting to box the impact of Aurat March into quantifiable evaluative categories, such as counting the number of attendees at a march, reduces a multifaceted movement to mere headcounts. This approach to evaluating success diminishes the value of the rich, transformative nature of collective action, overlooking the cultural and social shifts it inspires. Numbers are convenient for communicating impact because they fit neatly into existing frameworks. However, they erase the qualitative impact of the overall movement. Relatedly, prioritisation of media appearances or visibility can trap us in a no-win cycle where only the most sensational or easily digestible narratives get airtime, sidelining the organising work that drives structural change.

A reliance on these traditional metrics reflects a broader tendency to equate value with what can be measured or seen. This focus on visibility often overshadows the quieter dimensions of activism. This includes acts that sustain and strengthen the movement, such as the courage our cadres display while fighting patriarchal pressures within their homes and workplaces, the care we show for one another within our feminist communities, and the solidarity we enact across and beyond our collective. This culture of solidarity and mutual support is an aspiration in itself—a deliberate effort to reimagine how we relate to one another. It’s about creating spaces where individuals feel safe, valued, and supported, recognising that our collective strength grows from these relationships. These practices cultivate the slow and steady shifts in cultural consciousness—changes that might take years or even generations to fully manifest.

Aurat March Lahore embraces an approach that views social struggle as an ongoing process of change. As organisers and volunteers, our focus has always been centered on feminist consciousness-raising and building spaces for feminist organising that can nurture and sustain the feminist movement in the country. This approach acknowledges the evolving nature of the movement’s politics and strategies, shaped over time by diverse cultural, social, and political contexts. This evolution responds not only to external challenges of restrictive protest laws and digital surveillance, but also to internal needs such as dealing with burnout, ensuring political education, and working towards long-term sustainability of the movement. This allows us to focus on the experiences of our many communities, including our immediate collective, community volunteers, and the hundreds of people who march annually. Thus, viewing success as a process allows for a more holistic and accurate framework to understand the impact of our movement.

Our approach shifts the inquiry away from the obsession with tangible outcomes to the “constraints” and “affordances” that shape activists’ efforts to drive meaningful change. Here, change isn’t measured by external metrics alone but defined by our community through their lived experiences and interpretations of oppression and their shared aspirations for seeking change through our movement.1 It centers the voices of those directly affected, allowing their struggles, resilience, and dreams to guide how we understand and strive to create meaningful change.

******

For a movement that seeks to dismantle violent, capitalist, and patriarchal structures, what would we consider a win? Change, by its very nature, is systemic, gradual, and often difficult to quantify.

If the purpose of a movement is not only to agitate but also to create spaces of healing and transformation, then how do we measure such a process of unfolding? How do we quantify the experience of being confronted by art that bears stories of violence that survivors have never disclosed before? How do we capture the unquantifiable joy we experience when we irreverently chant feminist tappay together? These moments of courage, joy, and solidarity may not fit neatly into traditional metrics, yet they are powerful seeds of change. They foster emotional and cultural shifts that ripple through our communities, nourishing the soil from which larger systemic transformations can grow. These experiences remind us that change is not only about visible and immediate victories.

In the aftermath of revolutionary moments—such as the global ripple effects of #MeToo, the Baloch Long March, or the unprecedented solidarity at protests for Palestine—we dissect the complex reasons behind the change, teasing out whether it was a unique moment in time or the result of years of organising and hard work. We discuss how we could reverse engineer these moments of change. Every year, before 8 March, we write lengthy manifestos making demands of the Pakistani state, asking for accountability on issues ranging from economic inequality to enforced disappearances, only for these demands to be ignored. Each year, we ask ourselves: have we failed?

Failure as a part of movement-building

These questions bring us to a place of uncertainty. Is there a way to meet the urgent call for visible, measurable change—driven by the never-ending patriarchal violence and a yearning for justice—with the quieter/slower, long-term work of community building? How do we know if our solidarity is effective, and not mere lip service? How do we quantify our ongoing struggles that beget enduring and long-term efforts? As we navigate these complexities, perhaps the uncertainty itself can become a source of strength and a compass guiding us to collectively self-reflect. This ambiguity in measurement is not a shortcoming; it is a testament to the deep, reflexive, and soulful nature of activism.

Regardless, in any metric we choose to measure our movements, there should be humility, awareness of our limitations, and a quiet probing of why we rely on these markers. Is a movement still worthwhile if it fails to make tangible change? For organisers and volunteers, metrics can serve to understand ourselves and our mission. But do we need them to guide our direction?

We stand here, six years wiser, understanding that movements are imperfect. Aurat March Lahore may fall short of its promises, either because the world around it stands in opposition or because we simply lack the resources to enact transformational change. Perhaps in unlearning our reliance on traditional metrics of success, we must find new ways of introspection—training our instincts on feminist imagination, creating networks of solidarity, fostering joy and hope that inspires, building sustainable structures—and use these as our measures of success. We are learning to embrace failure as a function of movement building. We find humour in study circles that sometimes no one turns up to, while at the same time, we hold ourselves accountable enough to catalyse our creativity to better engage with our communities and wider society.

Aurat March has forced many conversations into the public sphere. The slogan “Mera Jism Meri Marzi,” first used at the 2018 march in Lahore became the flashpoint for the idea of bodily autonomy in a society where notions of “shame” and “izzat” shun such conversations into the private sphere. Though this slogan caused nationwide outrage and immense backlash, it also enabled conversations about women’s bodily autonomy and agency.

The movement solidified by providing safe, generative spaces for young women to come together and agitate against patriarchal structures. Alternative cartographies of emotional support were traced and coalesced by new relations forged amidst the collective struggle. Our movement continues to grow in surprising ways, and each year we have new volunteers bringing lived experiences to the March in unexpected ways.

Simultaneously, we recognise that the focus on groups like the Aurat March may overlook the efforts of other feminist organising in Pakistan.2 For instance, even though lady health workers stage their protests in the same physical spaces as us in Lahore, their demands for a living wage and work regularisation do not receive the same attention as we do. The Aurat March does not represent the entirety of the feminist movement in the country, but often serves as a shorthand for it. While we stand in solidarity with other feminist struggles, both domestically and transnationally, we continually experience the pressure to name and announce our support for each struggle, an expectation that sometimes outweighs our size and capacity.

As a movement emerging from visibility politics,3 we are also learning that visibility cannot be the sole marker of success. This year, fewer people attended the march in Lahore, offering us an opportunity to reconsider our priorities. With less visibility, we channelled our energies inward, fostering a space for internal growth and reflection. We dedicated our time to developing spaces for critical thought and reflection, like the Political School, “Siyasi Baithak,” in collaboration with WAF (Women Action Forum). The Baithak spanned four sessions and brought together over 25 feminists. These sessions fostered critical discussions on movement-building, allyship, sustainability, and the survival of feminist movements. The political school aimed to create a dedicated space for dialogue and action on key feminist issues, allowing participants to reflect on past struggles, explore contemporary challenges, and develop strategies to strengthen collective efforts. Discussions centered around ways to make the volunteering space of Aurat March Lahore chapter more inclusive of class and gender minorities. We also examined the methods employed by our allies and other feminist movements to make their collectives sustainable and assessed the applicability of those models to Aurat March as the March enters its seventh year.

Periods of quieter reflection are necessary to learn from past experiences and refine our strategies. This proved to be a valuable time for us to fortify our organisational structures, invest in training and education for our members, and build alliances with other groups. Fewer attendees at this year’s march might not be the failure we once thought it was. Rather, it has been an opportunity to engage in the deep work of building a movement that is not only visible but also capable of creating lasting change.

Shifting scale

When measuring success, we might then need to shift vocabularies and dig into other parameters which are not obscured by quantitative, NGOised criteria embedded in capitalist structures, nor, as Rafia Zakaria pointed out,4 informed by the white feminist gaze. By taking its sphere of experience as the only legitimate one, white liberal feminism has been defining what constitutes “real” change. It recognises resistance only in its overt acts of rebellion and ignores transformations which occur at an invisible, interpersonal level.5 It is through the emotional bonds we form that sustain our everyday struggle and strengthen our resilience against patriarchy, nestled within our families, workplaces, and society. Success, then, can be seen in the way our movements help transform our lives, establish mutual trust, and provide emotional support. These outcomes are visible only if we shift the scale to the micro-spaces generated by our coming together, where healing takes the form of celebration and mourning, where we can be loud when society silences us, where we forge solidarities that break the walls of isolation, trauma, fear, and violence.

We sign off collectively with our 2023 poster, a joint endeavour of two friends who have traced the contours of a new Lahore. Drawing from their intimate memories and dreaming together of alternative landmarks that could transform the city, the artists have replaced the aseptic military landscape with intimate forms of belonging and collective forms of existences. Building this collective, shared future imagined by Laiba and Aaleen is not easy–it requires time, resources, and un/re-learning. It is even more difficult to live up to our own feminist ideals. There will be and have been missteps. Nevertheless, our success lies in the process, an insistence on showing up despite these struggles and continuing to strive for the dreams we have envisioned for our collective futures.

- 68, 2003 – Issue 4. https://doi.org/10.1080/0014184032000160541.

↩︎ - Fouzia Saeed, “On Their Own Terms: Early Twenty-First Century Women’s Movements in Pakistan,” 2020.

↩︎ - Visiblity politics seeks to engender social change through “making the group’s collective identity and point of view publicly visible” according to Nancy Whittier. It is closely associated with tactics such as “coming out, social movement art, and media campaigns.”

Nancy Whittier, “Identity politics, consciousness-raising, and visibility politics,” in The Oxford Handbook of U.S. Women’s Social Movement Activism ed. Holly J. McCammon, Verta A. Taylor, Jo Reger, Rachel L. Einwohner. 2017.

↩︎ - Zakaria Rafia, “Against White Feminism: Notes on Disruption,” Penguin, 2021.

↩︎ - We borrow our understanding of the interpersonal, private struggles from bell hook’s framing: “All too often the slogan “the personal is political” (which was first used to stress that woman’s everyday reality is informed and shaped by politics and is necessarily political) became a means of encouraging women to think that the experience of discrimination, exploitation, or oppression automatically corresponded with an understanding of the ideological and institutional apparatus shaping one’s social status. As a consequence, many women who had not fully examined their situation never developed a sophisticated understanding of their political reality and its relationship to that of women as a collective group. They were encouraged to focus on giving voice to personal experience. Like revolutionaries working to change the lot of colonized people globally, it is necessary for feminist activists to stress that the ability to see and describe one’s own reality is a significant step in the long process of self-recovery; but it is only a beginning. When women internalized the idea that describing their own woe was synonymous with developing a critical political consciousness, the progress of feminist movement was stalled. Starting from such incomplete perspectives, it is not surprising that theories and strategies were developed that were collectively inadequate and misguided. To correct this inadequacy in past analysis, we must now encourage women to develop a keen, comprehensive understanding of women’s political reality. Broader perspectives can only emerge as we examine both the personal that is political, the politics of society as a whole, and global revolutionary politics.” Feminism: A Movement to End Sexist Oppression,” Feminist Theory from Margin to Center (bell hooks, 1984, p 24-25).

↩︎

Aurat March Lahore is a feminist collective based in Lahore since 2018. The collective is not affiliated with nor takes funds from any corporation, non-profit, or political party.